Marvellous malt

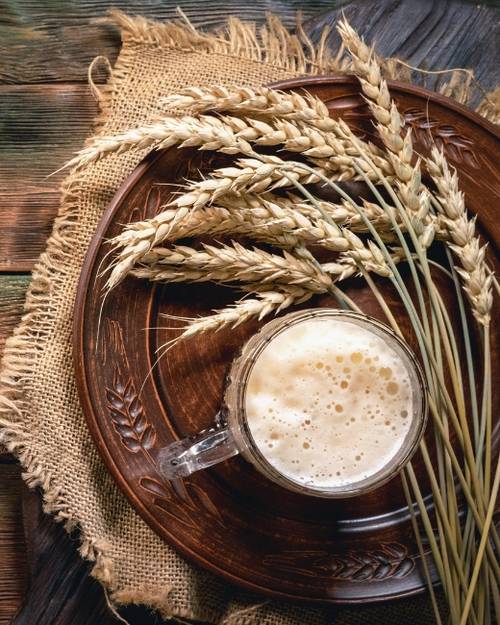

There may be a love affair with hops at the moment but without grain there is no beer. The sugars in grains provide the food for the yeast to convert to alcohol and carbon dioxide. The ‘grain bill’ or ‘malt bill’, the mix of grains used to make a beer, determines its colour and also gives it flavour and mouthfeel.

Other grains, such as wheat, oats, rye, rice or corn can be used, however barley is by far the most common. As its starch isn’t easily converted into alcohol through fermentation, the barley is malted, which converts the starch into the necessary sugars.

Malting involves seeping the barley in water which encourages germination (the sprouting of a root). The sprouting barley is moved to the malting floor or vessel where it is allowed to grow for four or five days while the moisture content and temperature are carefully controlled. This germination process converts the starch in the grain to the simpler sugars needed for fermentation, before germination is stopped by gently drying the grain in a kiln.

Varying the temperature at the kilning stage determines the colour and flavour profile of the malt. Basically, the higher the temperature the darker the malt becomes. This results in more complex sugars that don’t ferment – if you’ve ever tasted a caramel sweetness in a beer, that’s why.

It is down to malt and the time and skill involved in making its many variations that we have such a vast array of beer styles to enjoy today.